Switch off the editor's digest free of charge

Roula Khalaf, editor of the FT, selects her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“We are at 60 latitudes to the north. There is probably no one in the world that has darkness like us,” says Håkan Långstedt, Managing Director of Saas instrument in Helsinki-based architecture lighting. The company mantra “Protection of darkness”: a crusade against surveillance. In practice, it is an ethos that is classified as reserved, the light lighting in the “Chiaroscuro” in houses, hotels and private saunas at the lake and soon in the excitement of the National Museum of Finland. “You can easily destroy things with light,” says Långstedt. “Instead, we think of a pleasant contrast: how light fades into the dark. They want a transition.”

In a country in which the sun is on the horizon for several winter months, the decisive relationship between Finns has built in with light into its design history, from the ambitious masters of the 20th century to a new generation that constantly wires the landscape. Implementation is often a more subtle understanding of the lighting power of light.

In 1929 Alvar Aalto, an architect and designer who saw his work as part of a holistic company, received his career establishment commission for the Paimio sanatorium when he himself was taken to the hospital with illness. The Finnish designer later remembered the miserable view of a naked light bulb that hung over his sick bed, and later wrote: “My eyes turned to the electrical light, and there was no inner balance, no real peace in the room.” Alvar and the first woman Ainos Design for the sanatorium-one specially built tuberculosis facility in Westfinland, which was completed in 1933-is particularly important for lighting design: from the orientation of patient rooms to the capitalization of the full sunlight to the placement of overhead lamps behind the heads of patients to minimize. It laid the basis for the radical more humane modernism of the Aaltos and for the broader future innovation in Finland.

Four decades later, Aalto would unite his thinking in a late career masterpiece: Helsinkis Finlandia Hall. At the beginning of this year, the concert location reappeared from a three -year renovation, which were illuminated by Aalto's characteristic mixture of skylight with polished brass and around 2,000 lights that were cleaned and restored. The designer Mikko Kärkkäinen from Tunto Lighting, who is responsible for more than 700 of these newly modified equipment, sees his work in Continuum with the “balanced and brave” practice of the Aaltos.

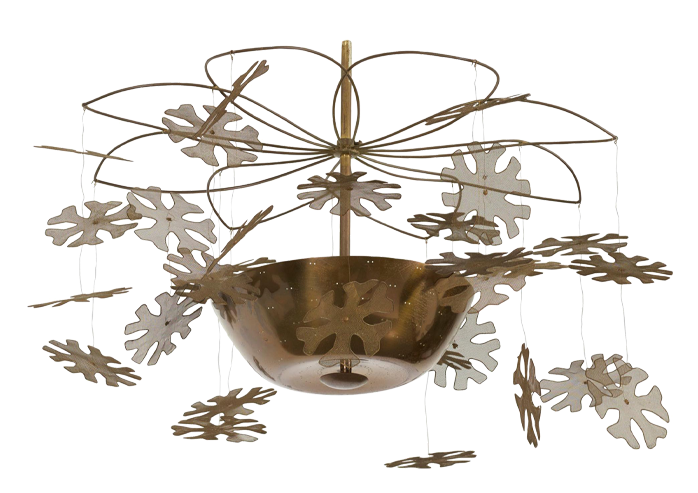

Many of the contemporaries of Aalto also forged shining careers in light design. Yrjö Kukkapuro (1933-1925), who died at the beginning of this year, is known for his Luminaires series YK100 (now available from the Swedish Lichtmarks Blonde), a design solution of the 1960s for its radical home. Paavo Tynell (1890-1973) is often illuminated as “the man who illuminates Finland” for his strikingly sculptural brass fittings, including the famous snow flake trailer. And Lisa Johansson-Pape (1907-1989), a multidisciplinary designer and co-founder of Illuminating Engineering Society of Finland, is attributed to functional, technical pieces with enamelled metal, acrylic and glass and many public hospitals and churches from Helsinki are changed.

For the aspiring generation, inspiration not only comes from this impressive design of the design, but also from a profound connection to seasonal rhythms of light and dark. “When spring comes north, you can feel how the energy level is increasing,” says prominent Finnish designer Joanna Laa.. “It is a very powerful experience.” Your approach is to compensate for architectural lighting with decorative equipment and to do often to warmer light tones compared to southern Europe. For the most recent Noa House project of the studio, a job in Helsinki, Laa.To has integrated her Ihana Lighting collection (designed for Marset) with Opal diffusers with Opal bubbles. “The effect is quite similar to a candle or even a fireplace. They create a soft ambience,” she says.

New design talent is also associated with craftsmanship and material -injured experiments. Hong Kong, Helsinki -based Didi Ng Wing Yins Wood Rasura Lamp is an offer for “naturalness”; Its meticulously carved grille made of ultra-thin semi-transparent wood chips and rice adhesive are set on a magenta-indicated ink stem, which is polished to reveal the grain. At Secto Design, Seppo Kohos is called Birchwood pendant pendant Kumulo and takes its form of cumulus clouds and snow-loving Lapland-Winterwald.

Hungarian born imola Balogh, whose grandmother practiced architecture in Finland at the end of the 1960s, recently began with a wood-based base, an innovative biomaterial that was developed by the Finnish packaging manufacturer Woamy. Early prototypes of their award-winning “Woodfoam lamp” leaned into the organic imperfection of the industrial process that describes “beautifully faulty” porous light filtering, as Balogh describes. “Research research in order to intentionally standardize these effects can open up new opportunities for future production.”

Tracking the new and respecting the past is an innate facet of Finnish culture. Partly a philosophy offered by the cycles of nature. “We are constantly expecting the pleasant sunlight of summer,” says NG. “The contrast tells me that I am patient.”

Perhaps this appreciation for everyday life goes hand in hand with Finnish satisfaction despite the probability of climate and latitude. “I love the temperature of light when it goes through the forest,” says Långstedt. “There is a promise in this light, a promise of something good.”

Find out first about our latest stories – follow @ft_houseandhome On Instagram